The Civil War was the bloodiest conflict in United States history; by the end, some 620,000 Americans lay slain on domestic battlefields. The two-day Battle of Shiloh on the banks of the Tennessee River saw more American casualties than all previous wars combined. By the end of it all, everyone was exhausted and most were ready for the conflict to be over.

When did the Civil War end? April 9, 1865 is the official date. That was the day that Confederate commander Robert E. Lee, cornered on all sides by General Grant’s army, capitulated. Lee signed the surrender paperwork in a small town in southern Virginia called Appomattox Court House. When the news hit the press, celebrations erupted across the North, but they quickly died down in the face of more violence. Let’s take a look.

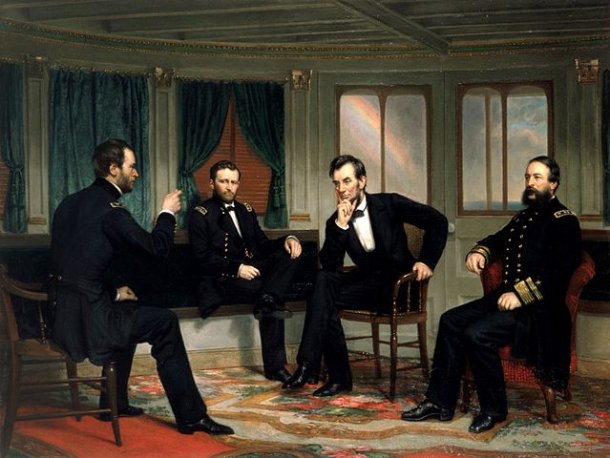

"The Peacemakers (1865)" - Sherman, Grant, Lincoln, and Porter pictured discussing plans for the last weeks of the Civil War (Photo credit: The White House Historical Association)

Revelry and Assassination

Upon hearing of the war’s end, Northerners from Chicago to Boston filled the streets, blasting rifles and lighting bonfires, toasting both peace and victory. The end of civil war saw impassioned patriots burning effigies of Southern generals and throwing horse dung at their likenesses. Streamers flew from public buildings, and a profitable cottage industry hawking little American flags took off.

But the postwar joy would be brief. Before the week was out, a Confederate bomb plot was caught at the last minute, someone tried to stab the Secretary of State in his bedroom while he slept, and President Lincoln was shot and killed by assassin John Wilkes Booth.

Jeff in Petticoats

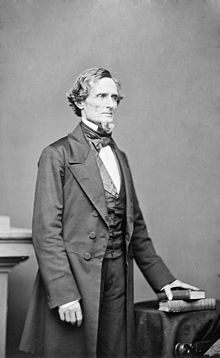

Jefferson Davis - President of the Confederate States (Photo credit: Brady National Photographic Art Gallery)

The furtive government-in-exile had in fact been planning a renewal of the South’s cause, but the manhunt was carried out because the War Department mistakenly believed Davis had helped plan Lincoln’s assassination.

The news of his arrest sparked celebrations across the North, while the press proclaimed Davis the traitor to Lincoln’s martyr. He was widely mocked in the wake of a nasty rumor that spread like wildfire, accusing him of fleeing dressed in women’s petticoats.

Yet, after just two years in prison for treason, Jefferson Davis was released on bail for $100,000. The bail was paid to “deafening applause” in a spirit of national reconciliation by a motley crew of prominent abolitionists and industrialists. Davis later went on to become an insurance salesman.

The Strange Tale of Wilmer McLean

Wilmer McLean's residence in Appomattox, photographed in 1865 (Photo credit: Library of Congress website)

In 1861, McLean lived right off the main road linking Washington D.C. and Richmond, the respective capitals of the divided North and South. This proved a serious real estate blunder when the first battle of the Civil War broke out right on his doorstep. It was the First Battle of Bull Run.

During the battle, Wilmer’s home was commandeered by a Confederate general for use as a headquarters and hospital. The house sustained volleys of gunfire and cannonballs, including one that smashed his kitchen up after a mysterious fall down the chimney. By some miracle, he and his family survived the ordeal.

Yet, McLean didn’t rush to leave town—at least until the following year, when the much larger and bloodier Second Battle of Bull Run exploded around him. No longer feeling so lucky, McLean finally left with his family to resettle further south, over 100 miles from the fighting in the town of Appomattox Court House, Virginia.

All was quiet for a few years—until General Grant pushed Robert E. Lee’s Army into southern Virginia and trounced his ragged forces. Lee signed the papers that ended the Civil War in none other than Wilmer McLean’s own parlor.

“The war began in my front yard and ended in my front parlor,” he wryly noted as the generals went their separate ways.

Bonus Facts To Arouse Your Curiosity###

The War After the WarThe postwar period was an embattled era in its own right, marked by a sustained military occupation and rampant domestic terrorism by groups like the KKK. The U.S. military occupied the South to implement Reconstruction in rebel territory amid this violence. It did not go over well with Southern whites, whose bitterness over the occupation lingers to this day.

NRA vs. KKK

The National Rifle Association, or NRA, was born at the end of the Civil War to teach marksmanship, but it quickly grew into grassroots social justice organization amid the upswell of racist violence during Reconstruction. NRA members set up chapters across the South to help train freed Black slaves to defend themselves from the KKK with minimal bloodshed.

Safe Passage

The day after Lee surrendered, he and General Grant returned to Wilmer’s fateful parlor to discuss the safe passage of Confederate soldiers. There, Lee secured over 28,000 “parole passes” for rebel fighters to carry as they made their way home, ensuring they would not be arrested en route.

Delayed Reaction

While Lee had capitulated in the heart of the conflict, a few on the periphery didn’t get the memo, and others simply ignored it. From Alaska’s shoreline to the French Normandy coast, several sea battles simmered abroad in the months after Lee admitted defeat. The true last shots of the war were fired by Confederate sailors on the CSS Shenandoah, in the icy waters of the Bering Sea near the Arctic Circle.

Slavery is Dead! Sort Of…

When the Civil War ended, a package of exemptions left nearly 300,000 slaves in bondage even in areas controlled by Union forces. And later, to spite the Yankees, a few states kept slavery legal even after the 13th Amendment was ratified. Kentucky held out until 1976—over a century after the end of the war.