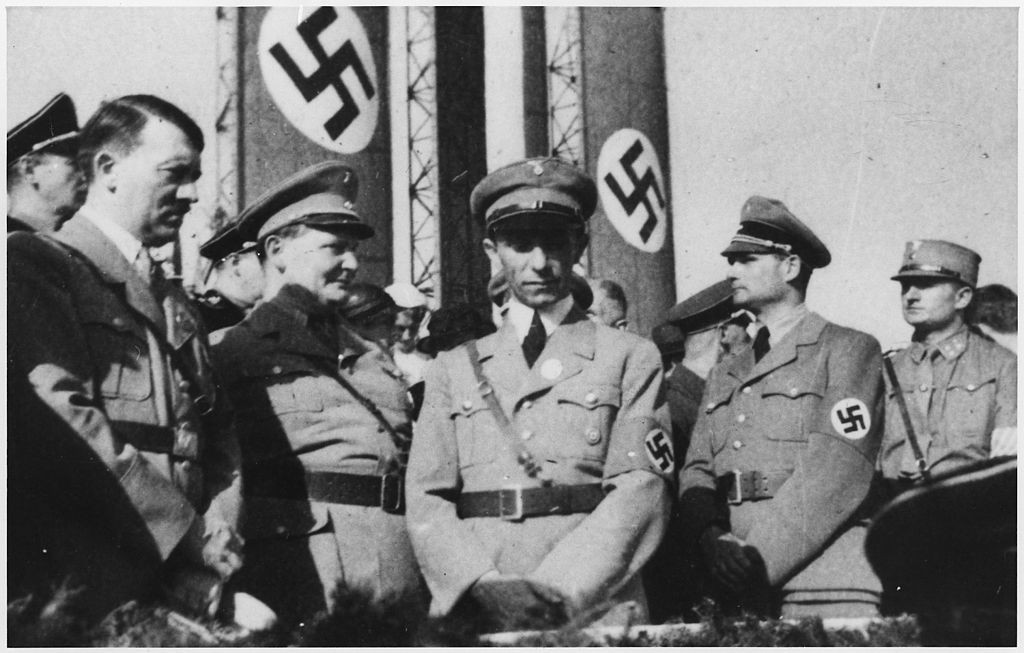

Archives and Records Administration) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

While it is customary to assign specific start and end dates to historical events, the reality is always more complex. The Holocaust is a case in point.

Though it is associated with World War II, the ideology and infrastructure of the genocidal program were seeded in the preceding decade. The lead-up to war and genocide during the 1930s was an essential precursor to the the Holocaust and must be understood as its foundation.

“The Holocaust” usually refers to the mass murder of civilian Jews by the German Nazi regime that occurred during World War II. In this sense, the start of the Holocaust symbolically began upon the Kristallnacht of 1939. The “Final Solution to the Jewish Question” was launched a few years later.

The Holocaust did not end until 1945 when foreign troops finally defeated Nazi forces and freed survivors in the camps.

The Historical Context: Interwar Chaos

To understand the start of the Holocaust, we must go back to 1933 - the year Adolph Hitler and his Nazi Party assumed control of Germany. The anti-Semitic project that became the Holocaust was born and died parallel to Hitler’s tenure as the head of the German state and Nazi empire.

Early in 1933, the Nazi propagandist and politician Adolph Hitler was named chancellor of the German Republic following elections in which the Party fared well. His appointment marked the ascendancy of German fascism, which established its hold on German politics following the 1929 crash of the global economy.

The year 1933 was dogged by civil unrest. The Great Depression had become entrenched. There was mass unemployment. The government was in disarray; competing political factions fought bitterly in an increasingly polarized atmosphere. These conditions lended credibility to demagogues who publicly blamed minorities such as the Jews for the nation’s woes. Ultimately, the Holocaust would seek to eliminate these people for good.

Foundation of the Holocaust: The 1933-1938

Within weeks of taking office, Hitler gave the green light to the elite SS guard to construct and operate a concentration camp just a few miles outside the busy city of Munich, near the rural Bavarian town of Dachau.

Dachau was the first Nazi concentration camp and the most important in the early years of National Socialism. During the pre-war period, more than 100 local concentration camps of varying sizes were set up. Their purpose was not extermination, but general repression and containment.

Hitler’s budding fascist dictatorship first deployed the sites as prisons for dissidents who denounced the regime, especially political leftists. In 1935, the state broadened the scope and began to target minorities deemed racially or biologically inferior.

In 1938, the treatment of Jews took a violent turn. In winter of that year, the government deliberately incited a pogrom against Jews across Germany and Austria. The Kristallnacht, or Night of the Broken Glass, saw the merciless destruction of Jewish homes and businesses, torching of synagogues, murders in the streets, and mass arrests of the victims. Some 90 Jews were killed in the streets by vigilante mobs or in police custody at the hands of security forces. In the aftermath, some 30,000 were sent to labor or languish in the concentration camps.

While the Jews had been persecuted in preceding years, the pogrom signaled a new, bloody phase in the Nazi project. As a result, some people consider this frenzy of state-sponsored terror the true beginning of the Jewish Holocaust.

Laboratories of Terror: 1939-1941

As early as 1937, the Nazis began to scale up their carceral capabilities. But the largest expansion came with the official onset of the war. The upgrades were needed to accommodate the growing tide of prisoners streaming out of Nazi-occupied Austrian, Slovak, Czech, Polish, Russian, and other lands.

Poland in particular was designated the Nazis’ laboratory of racial policy in the European theater. It was during the 1939 Nazi invasion of that country, which triggered the beginning of World War II, that high-level officials in the Party first crafted the idea of “demographic engineering” amid escalating atrocities in the occupied territories.

But it was not until the invasion of the USSR in late 1941 that a conscious policy of systematic, Jewish extermination was articulated and implemented. The invasion of Russia, dubbed “Operation Barbarossa,” was declared a war against the “Jewish-Bolshevik intelligentsia” and Nazi troops were ordered to slaughter all the Jews they could find. By the end of the year, an estimated 800,000 had been killed.

Although it was not called or planned as a campaign of extermination, this campaign is generally considered the beginning of the so-called “Final Solution” policy.

Industrialized Genocide: 1942-1945

After Barbarossa, the Nazi brass enthusiastically embraced the new focus on large-scale termination. In 1942, the so-called “Final Solution” policy was formalized as a key pillar of the war effort. The term “Final Solution” was Party apparatchiks’ preferred euphemism for their plan to liquidate the Jewish population of Europe.

Soon afterward, the extermination camp now known simply as ‘Auschwitz’ opened and began accepting prisoners. Eventually, a total of six extermination camps were established as an extension of the vast established network of concentration camps, which numbered in the thousands.

Equipped with gas chambers to carry out executions en masse, quickly and with efficiency, the extermination camps epitomize the Final Solution and comprised its principal workhorse. By the end of the carnage, the Nazi-driven Jewish Holocaust saw the slaughter of nearly two-thirds of the Jewish population of Europe.